Hackathons. It’s one of those words that seems to be cropping up a lot in education these days. I initially thought it was something to do with software development. With distant memories of Douglas Coupland’s Microserfs, I pictured young, mostly male coders typing intensely into the small hours of the morning, fuelled mostly by pizza and (an admittedly biased view) a geekish love of programming. In this blog post I will try to offer a different perspective by reflecting on a rather different sort of Hackathon experience, wearing the hats of both learner and academic developer.

This motivation to learn more about Hackathons has come from the fact that DCU is engaging in a major curriculum transformation project – DCU Futures – which includes Challenge Based Learning (CBL) as a key pedagogy. CBL is fundamentally about the investigation of real-life problems related to pressing societal issues. It is a pedagogical approach that is increasingly being used in higher education to foster transversal skills, increase knowledge of socio technical problems, and enhance collaboration with industry and community stakeholders (Gallagher & Savage, 2020). A hackathon is one example of CBL in practice but it can take other forms including projects, design events, or competitions that aim to solve difficult problems. Lyons, Brown & Donlon (2021, p.1) describe a hackathon as an ‘intensive run’ where participants commit to forming collaborative teams to resolve and present solutions to real-world challenges during an allocated period of time.

Most of us in Higher Education are completely new to the notion of Hackathons and even fewer of us again have actually organised one. Since supporting the design and implementation of CBL is part of the Teaching Enhancement Unit remit, it seemed important to get an authentic experience on how this approach might work. There could be no better way to ‘walk in the shoes of students’, than to get a first-hand experience of a Hackathon for myself.

The opportunity to get that experience came in the form of a recent weekend event for postgraduate research students with DCU Institute of Education called ‘Hack to Transform’. As a current DCU EdD student, I was thus able to join a ready made, well-organised, educationally-oriented event where I would hopefully get a good sense of how such things worked. Organised by Dr Gillian Lake, PGSR Programme Chair, this newly hatched Hackathon was described as follows:

A hackathon is a creative problem-solving event. In this event, research students come together to solve/hack an education challenge for the 21st Century, in just two days!

While not initially enamoured of the idea of giving up most of a weekend for this (yes, I did have to think carefully about the commitment as I’m glad to report that I do have a life), curiosity prevailed and I signed up.

How the Hackathon Happened

It took place Nov 26th and Nov 27th. It was all done entirely on Zoom (3.5 hours on Friday evening and 10.5 hours on the Saturday) and there were 15 of us taking part. Several of these were Phd or EdD students but there was also a good smattering of nosy support staff and academics on board. So what exactly did we do?

Approximately one week before the event we were given the title of the challenge: “How can we ensure the most effective educational experience for all in the 21st Century?”. We were asked to come up with a 60 second pitch for how we might solve this challenge. The ask was to pitch our ideas to fellow competitors to get them to come on our team. We were given guidance that pitches were to be no more than 60 secs long and no slides were allowed. The idea was that based on the five most popular pitches, participants would self-select their teams. On the Friday evening, we voted for the top pitches to whittle down the list. Then everyone self selected to the pitch that resonated most with them and the teams were born.

My own pitch on building a university policy that commits to meaningful student contribution to the design of every single new course from September 2022 was not successful (boo hoo!) but I did get to join my colleague Rob Lowney’s team which also had a HE focus and a student partnership angle. Rob had the idea to develop a data warehouse and dashboard solution that integrates educational data within DCU to empower students and staff to plan for the future. Emma Gallagher, Teaching Fellow at DCU also joined the team, bringing her much-needed second-level perspective to the table. Other tempting pitches included the development of an open multicultural space (“pocket of community”) for vulnerable communities and non-students in the university environment; development of holistic, multiple intelligence assessment processes; and the use of more playful “FUNdamental” learning experiences in education.

With the teams all sorted, things kicked off bright and early on the Saturday morning with a very full timetable for the day. Over the course of the day we needed to develop a persuasive problem statement, work with a designated mentor, and ultimately create a solution that would win over a judging panel. Through various pep talks and videos, it was made clear to us that we needed to come up with a clearly stated problem, an innovative solution, and a creative presentation by 5.15 pm that day. We were advised to think about roles within the team and take heed of the advice to understand the ‘who’ (Who are the people experiencing the problem? How will this solution make their lives better?). We were warned that slides were off limits and given the judging criteria which would be based on our agility in response to the task, our innovation, our focus on a real-world problem and solution, and our presentation skills.

Mentor Advice

Our team was very lucky to land the mentor of Ciaran Flynn, founder of Child Paths who challenged us to identify our Unique Selling Point (USP) and define what success would look like. Ciaran asked us to research if there was something similar available elsewhere, narrow down the problem and write our proposal in simpler terms.

He highlighted various aspects from Design Thinking including:

- Need to show how our intended audience will benefit (EMPATHY)

- Need to define and condense the problem (DEFINE)

- Identify when we will know if the solution is successful – was there anyone we could connect with to see if this was a real-world problem and solution? Could we call on a student, for example? (IDEATE)

- Would it be possible to present this visually? (PROTOTYPE)

- Ask colleagues for feedback (TEST)

- Prepare a compelling presentation of the solution, using the principles of storytelling (LAUNCH)

He also encouraged us to have confidence that our solution will work, try to avoid making assumptions and consider ‘before and after’ perspectives in order to drive home what was going to change by having students more involved in the process. He highlighted that it was important to identify markers of success, highlight our own expertise in the space, and also ensure that the USP of the solution was visible and clear. Alas ours was not the winning team at the end of the day (kudos to the FUNdamental team for a seriously good solution and pitch) but the learning from this experience was immense.

Pros and Cons to My Hackathon Experience

On the plus side:

- Coming up with a 60 second pitch was relatively easy and enjoyable

- The idea the team worked on was definitely innovative – there’s nothing like this out there at the moment and it was something that we all could contribute to in different ways.

- We collaborated closely and we did end up allocating areas of responsibility – we set up a Whatsapp, worked well on the central Google Docs and on Zoom, and kept a sense of humour most of the time (although I admittedly was feeling a bit stressed with the rush to get things done in the afternoon.)

- We talked through what the problem solution could be and we gained insights into second-level and third level perspectives

- We definitely were Agile, moved quickly, and listened to each other – we struggled with how the presentation should start but negotiated this and the role play idea (which allowed sharing of student and staff perspectives) turned out to be a really good fit. It also allowed us to bring our personalities to the process, which was a real bonus.

- We were not afraid to challenge each other – eg We pondered the connotations of Sure Things (!) as a title for our tool and we did negotiate over the best presentation format

- Our presentation was actually fun – people seemed to respond well and I, for one, enjoyed the role play aspect and plan to use that again in teaching and presenting.

All team members were natural collaborators.

All had an interest and belief in student partnership in education.

All were technically adept and open to change.

On the ‘could have gone better’ side, with the benefit of hindsight:

- We probably rushed the scripting part of the presentation because we ran out of time to prepare that part of the day.

- We didn’t bring all the perspectives we had researched to the table – in my own case, I felt I could have played more on the input of the student and National Forum expert views I had collected. In retrospect, instead of collecting these elements privately, I could have made more use of Twitter which would have made this more visible.

- Possibly most importantly, I suspect we probably took on a complex problem that needed more time to refine the message.

In other words, it turned out that we needed more time to explain what was a complex proposition in the script. While we were asked to ‘Think Big’ I think perhaps it was too much to attempt to explain the benefits of student partnership, the potential value of learner analytics, AND introduce a never-seen-before dashboard in role play form in 6 minutes. Rob did a super job in explaining the tool and creating a mock up prototype and Emma scripted and acted a wonderfully authentic student voice but I think we took on a very big task to be clear, succinct and informative on the core USP of the process and dashboard. I believe that my academic voice could possibly have been more critical (I’m not sure all academics would have responded quite as positively as the role play suggested!). This all might have been possible if we had allowed more time to refine our message, perhaps focusing on three key points (eg the three particularly useful and topical pieces of data of direct relevance to the students). This had been suggested earlier but possibly got lost in the frenzy of activity and questions.

In retrospect, we actually did come up with a clear problem statement and with more time, would have incorporated this further:

What is the problem?

University curricula are key to enabling 21st century skills. But university processes for renewing curricula are stuck in the 20th century. A 5 yearly curriculum review is not agile enough to meet the 21st century skills agenda. We need constant reflection on and refinement of our curricula to meet ambitious 21st century targets set by supranational and national policy centres.

The student voice needs to be at the centre of it and it needs to be an informed and empowered voice. Let’s make it easy for students to reflect on their educational experience by giving them ownership of their learning data, through an opt-in data dashboard. Then give them a seat at the table to tell staff what it’s really like on the ground so staff can refine the curricula with up-to-date information and experience.

A Concluding Top Ten

But it was never really about coming up with the perfect solution under such conditions and really my personal takeaways are more about what the lessons are for the future – and sharing what might be of use to other educators planning to integrate Hackathons in some way into their teaching. This is just one perspective on one event, of course, but in no particular order, my top 10 takeaways are as follows…

- I learned that Hackathons, done well, can be a hugely powerful approach to addressing challenges and I may be something of a convert – even without pizza.

- They seem to get a lot done in an extraordinarily short period of time and could act as a stimulating kick start to projects. However, the problem needs to be appropriate to the timescale and students need a lot of support in identifying and refining essential questions to be answered.

- They are ideal for rapid group work – but they assume a motivated group who don’t have any group work baggage and are ready and able to work together as a team. We could have used Belbin’s team roles, potentially, or other group work preparatory tools.

- More time for individual work would have benefited us and there is very little space for this in such a tight timeframe. Part of me knows that for introverted types, a Hackathon could be hell on earth (at least initially). Can anything be done to make Hackathons both challenging AND inclusive? Or is the discomfort half the point?

- I also strongly believe that a follow up reflective component is essential as there is much to parse from the event and that could easily be lost without adequate time to reflect.

- The time management component seems essential – especially when trying to do something novel and creative. Students and staff are likely to need support with this.

- It promoted creativity and I for one loved the role play dimension – I think it would have been very difficult to showcase staff AND student perspectives without thinking differently in the presentation.

- Might there be a way to thrash out the problem and solution more efficiently? Perhaps being told you’ve got to come up with the three main problems and the solution that would address those might have helped? What support does the mentor need to help participants tease these out?

- Yes, time ran away with us and it is pretty exhausting but I am not sure if I can move any faster!!! I’m not 20 – but then again, I’m not really the target audience for most Hackathon events.

- Finally, most of us working in academic development are definitely not in our comfort zone with this approach – but if you get the chance to participate in something like this, go for it and draw your own conclusions for yourself.

References

Gallagher, S.E. & Savage, T. (2020). Challenge-based learning in higher education: an exploratory literature review. Teaching in Higher Education, DOI: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1863354

Lyons, R., Brown, M., & Donlon, E. (2021). Moving the hackathon online: Reimagining pedagogy for the digital age. Distance Education in China, 7, [English Version].

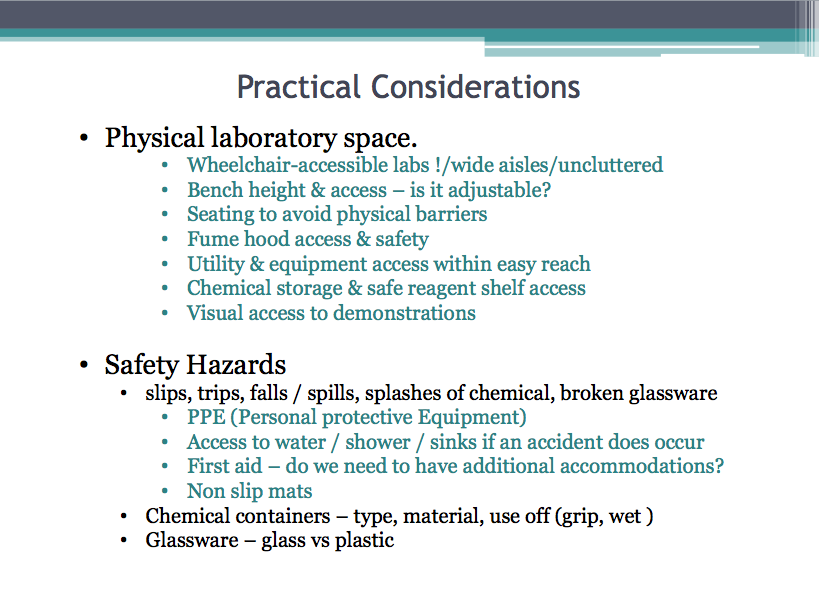

With an emphasis on safety and the achievement of positive and successful learning outcomes for all students, Veronica outlined the kinds of accommodations that are being made to include students with disabilities in laboratory practicals. This conversation really drove home for me the ‘high stakes’ nature of the issues here given the presence of sometimes dangerous chemicals. For example, there may need to be discussions about whether a 1:1 lab assistant may be needed, there is a definite need to discuss and agree a proposed approach with students, and there are clearly availability/cost questions involved. Other simpler measures include the possibility of using preferential seating to reduce the level of extraneous stimuli, the provision of support for frequent practice, and inclusion of brief breaks throughout the practical as appropriate. It was also fascinating to hear about creative and thoughtful efforts such as the creation of a wheelchair-friendly ‘lab coat’ that could be removed quickly and safely if needed.

With an emphasis on safety and the achievement of positive and successful learning outcomes for all students, Veronica outlined the kinds of accommodations that are being made to include students with disabilities in laboratory practicals. This conversation really drove home for me the ‘high stakes’ nature of the issues here given the presence of sometimes dangerous chemicals. For example, there may need to be discussions about whether a 1:1 lab assistant may be needed, there is a definite need to discuss and agree a proposed approach with students, and there are clearly availability/cost questions involved. Other simpler measures include the possibility of using preferential seating to reduce the level of extraneous stimuli, the provision of support for frequent practice, and inclusion of brief breaks throughout the practical as appropriate. It was also fascinating to hear about creative and thoughtful efforts such as the creation of a wheelchair-friendly ‘lab coat’ that could be removed quickly and safely if needed.